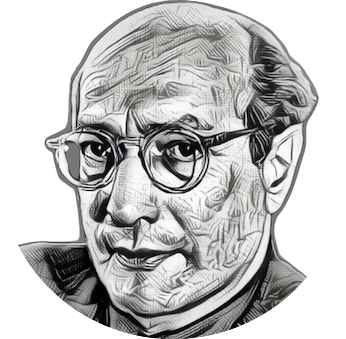

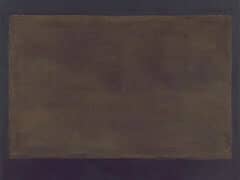

The Omen of the Eagle, (1942) by Mark Rothko

Rothko in 1940-42 began a series of pictures inspired by mythological themes, especially from Greek myths. They sought out archaisms to which the war lent metaphoric potency. In "The Portrait and the Modern Artist," Rothko wrote: "Those who believe that the world today is less brutal and ungrateful than in these myths, with their overwhelming primeval passions, are either unaware of reality or they do not want to see it in art." The choice of mythological themes at the same time was an attempt to take on universal questions. Rothko were interested in Interpretations of Dreams by Sigmund Freud and C.G. Jung's theories of the collective unconscious, in addition to having read the ancient Greek philosophers. Rothko was fascinated by Plato and by Aeschylus's Oresteia, which he adapted into several episodes.

Rothko's archetypes depicted barbarism and civilization, dominant passions, pain, aggression and violence as primeval, timeless and tragic phenomena, without needing to take a position on the war as a historic event, playing instead with history on the metaphoric level. The multi-layered significance is evident in two of Rothko's statements on The Omen of the Eagle:

The theme here is derived from the Agamemnon Trilogy of Aeschylus. The picture deals not with the particular anecdote, but rather with the spirit of myth, which is generic to all myths of all times. It involves a pantheism in which man, bird, beast and tree, the known as well as the knowable, merge into a single tragic idea."

The eagle was and is a national symbol for both Germany and America. Americans saw the war as a conflict between barbarism and civilization. Rothko united that savagery and civilization into a single barbaric figure that embodied aggression and vulnerability in one, the figure of the eagle. Asked again about the work in 1943, Rothko spoke simply of "the human tendency to slaughter each other, something that we know all about today." Rothko's biographer, James Breslin, said that he wanted to depict what "he liked to call the 'spirit of the myth,' not the Greek or the Christian subject matter, but the emotional roots, the essence of the myth that is effective across cultures."